photos by olga kowalska

The end of the 1930s was a watershed moment for Chrysler. Which revolutionary model, new line of cars, new engine or new production milestone occurred back then you may ask? It’s hard to believe but it was even more fundamental than any of that. It was in fact when Walter P. Chrysler made his last motorcar, for the man himself died in 1940 after suffering a stroke in 1938.

What you see here is Walter P. Chrysler’s ultimate creation – the 1939 Chrysler Imperial, one of approximately 3,000 built that year and one of 46 exported to Australia.

The era marked an important transition for the whole auto industry. Overall production capabilities would be utterly transformed in the coming years by World War II. If Henry Ford’s techniques marked the transition from ‘craft’ to production, WWII and in particular the period of reconstruction afterward marked the transition to mass production.

The end of the ‘30s was also the high water mark for the art-deco movement and Richard and Serena Breese’s ’39 Chrysler Imperial has no shortage of detail as evidence of that.

The Imperial nameplate ran from 1926 until 1983, though from 1955 it was a standalone make in line with its Cadillac and Lincoln rivals. The Imperial was briefly revisited from 1990 to 1993 and a concept Imperial based on the 300C appeared at the Detroit Motor Show in 2006. In 1939 the Imperial was the flagship model of Chrysler’s premier division.

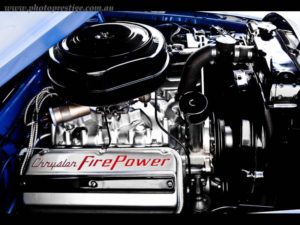

This ’39 Imperial is motivated by the 323.5 cid flat-head straight eight engine developing 135 horsepower. When Richard and Serena bought the car in 1976 as a fully registered road-going driver the engine had been bored out beyond 350 cubes. During the restoration which began in 1992 Richard had the block sleeved, bringing it back to its original 323.5 cubic inches. It’s a decision he now has mixed feelings about as, while the Imperial is no slouch, it resulted in notably less ponies. “There’s no substitute for cubes,” says Richard.

Around 1979 Richard heard rumour of another Imperial in a forgotten paddock out in the  country. That car was in a bad way but incredibly when he looked at the engine number it was the very next one off the line after his. Richard and Serena have that engine in their garage today.

country. That car was in a bad way but incredibly when he looked at the engine number it was the very next one off the line after his. Richard and Serena have that engine in their garage today.

For many years they used the Imperial like a second family car, took it on family trips, even towing a caravan on occasion. They’d put more than 70,000 miles on it when a worn radiator took them out of Australia’s classic Bay to Birdwood run in 1992. Once they started pulling it apart to repair the radiator they decided to keep going with a full restoration.  Richard alone put in an incredible 2,140 hours. “Serena would say – surely that’s enough,” says Richard, as he painstakingly filled and sanded panels over and over.

Richard alone put in an incredible 2,140 hours. “Serena would say – surely that’s enough,” says Richard, as he painstakingly filled and sanded panels over and over.

While working on the front left guard Richard found a curious section which had been cut out and superbly patched. It wasn’t til later he found out this was the result of a charcoal burner, a common fitment during WWII gasoline rationing.

The interior was re-trimmed using the Imperial’s original art-deco designs. Richard pulled together a complete set of instruments in satisfactory order. With a good clean up they were re-fitted and retain all the charm of a car that has been in regular use for the greater part of its 72 years. The result is an interior swathed in art-deco panache.

The interior was re-trimmed using the Imperial’s original art-deco designs. Richard pulled together a complete set of instruments in satisfactory order. With a good clean up they were re-fitted and retain all the charm of a car that has been in regular use for the greater part of its 72 years. The result is an interior swathed in art-deco panache.

As the US climbed its way back out of The Great Depression cars like the ’39 Imperial were an audacious statement. Even the name ‘Imperial’ set the scene for the America that would emerge over the following decades.  This ’39 Chrysler Imperial is a statement of what in those days was American aspiration. It’s only with the value of hindsight we can look at it as a harbinger of days that were to come.

This ’39 Chrysler Imperial is a statement of what in those days was American aspiration. It’s only with the value of hindsight we can look at it as a harbinger of days that were to come.

1939 Chrysler Imperial C23 Specs

ENGINE: 323.5 cubic inch side valve inline 8 cylinder. Bore 3 ¼ inches. Stroke 4 7/8 inches. Compression ratio 6.8 to 1

POWER: 135 HP (101kW)

WHEEL BASE: 125 inches

TRANSMISSION: Borg Warner 3 speed with overdrive, syncro on 2nd and top.

SUSPENSION FRONT: Independent coil, pantograph type. REAR: Semi-elliptic leaf springs

BRAKES (hydraulic) FRONT and REAR: 12 inch diameter drums x 2 inch width shoes.

WHEELS AND TYRES: 700 x 16 inch light truck radials

PERFORMANCE: Top speed in excess of 100 mph.

KERB MASS: 4080 pounds (1854 kg)