The taxi turned into Allée des Deux Trianons, Versailles, at precisely 7:30, fitting into a long line of cars offloading passengers in turn at the Grand Trianon. The line of cars moved ahead slowly as more than one limousine lingered at the disembarkation point for its celebrity occupants to make an ‘entry’ before the Grand Trianon’s peristyle.

“Come on, let’s walk,” said Felicity  as their taxi inched along. “We can take a shortcut through Marie Antoinette’s Estate.”

as their taxi inched along. “We can take a shortcut through Marie Antoinette’s Estate.”

“Is that allowed?” said Alan, frowning unsure.

“Excellente idée” said Gerome, already handing a large note to the taxi driver.

They climbed out of the taxi, and when it u-turned conspicuously out of the queue Felicity had already thrown her Christian Louboutins over and was now climbing the fence. “We can cut through the gardens,” she said.

“Here, give me a boost,” said Gerome to a bewildered Alan, who nonetheless leaned down and linked his hands to offer his boss a lift.

Now that the precedent was set, after a moment’s thought occupants of several other vehicles began disembarking right there on the long gravel drive amid playful conversation and laughter. A few followed Felicity’s lead and climbed over the fence to enjoy an early evening walk through the garden, but most preferred to walk along the tree-lined drive up to the Grand Trianon.

Two thirds of a moon cast just enough light to navigate the garden path. They crossed a small bridge and passed a domed marble structure that Alan thought captured the moonlight magically.

“Le Temple de l’Amour,” Gerome commented.

They stopped briefly and looked up at it before they continued on. The path wound alongside what appeared a narrow pond of water-lilies, eventually coming upon a more grand structure, lit up to magnificent effect.

“Le Petit Trianon,” said Gerome.

“Built for Madame de Pompadour,” explained Felicity, “…Louis XV’s favourite squeeze.”

The gardens from here were more formal and lit all the way up to the Grand Trianon. Felicity and her two gentlemen led a few small groups along a broad gravel avenue, past flowerbeds and wide ornamental pools, and past the ‘French’ Pavilion. Mirthful conversation mingled across groups of strangers, adding a sense of festival to the whole event.

They reached the Grand Trianon with at least a dozen cars still waiting to disgorge their dazzling occupants.

Walking straight past the peristyle across which all the fabulous attendees were making their splendid entrances, they made their way instead directly to the Garden Room where a jazz quartet entertained guests spilling out down the steps and into the garden where trays of champagne and hors d’oeuvre were circulating.

“Gerome you sly bastard,” somebody called out. Gerome turned to greet the man with an enormous smile and amid a lot of back-slapping, hand-shaking and “Ça va?” and “Ça va! Ça va bien!”, Gerome introduced Felicity and Alan to Frederic Oudea, Deputy Chief Financial Officer at Société Générale. The schmoozing was underway in earnest. In fact Gerome seemed to know half the well-heeled charismatics at the party, industrialists and politicians, movie stars and recording industry execs. The representatives of various NGOs and charities circulated, like classy whores in a first class brothel or hyenas round a slaughtering pen Alan couldn’t make up his mind.

Doctor Beauvoir seemed to take to it naturally, slipping easily into jovial banter with complete strangers, many of them well-known identities and some of them simply oozing status and wealth. Noticing that Alan was less than comfortable in this environment she drew him into conversation more than once, and proved so adept at this that Alan could almost have believed himself a natural raconteur.

Pretty soon guests were asked to make their way into the Cotelle Gallery, where almost its entire fifty metre length was consumed by a row of four great dining tables, each resplendent in full formal setting beneath the famous Montcenis chandeliers. A small platform with a rostrum had been placed to one side midway along the Gallery, just high enough so that all guests could see the speaker. Places were labelled and Gerome, Felicity and Alan found themselves seated directly to the right of the rostrum amid Liliane Bettencourt with her chaperon, eighteen year old grandson Jean-Victor Bettencourt-Meyers, and the year’s pop princess, Jenifer Bartoli.

While other guests began taking their seats Madame Bettencourt, resplendent in majestic Givenchi dress and Cartier jewellery, remained standing, grandson diligently at her elbow, in steady conversation with Gerome and two other dignitaries.

“André sends his regards, Gérome. He always said how thankful he was to have you and Lionel over at Parnibas. He appreciated your expert service and your excellent advice.”

“I‘m sure Gérome feels very fortunate for the association with Monsieur Bettencourt and L’Oreal too, Liliane. The bankers do alright for themselves with our money, and you certainly have plenty of it for them to do alright with,” said Jeaneé Plantin, UNESCO Assistant Director-General and Mistress of Ceremonies for this evening’s event, raising a few chuckles from everyone except Gerome.

“Ouch, that stings,” said Gerome. “See the level of respect I get Berglind?” he implored OECD Deputy Secretary-General, Berglind Ásgeirsdóttir. “I don’t recall UNESCO ever complaining about the bank’s support, or L’Oreal’s for that matter,” he added with a nod at Madame Bettencourt.

“I feel it too, Gérome,” said Ásgeirsdóttir smirking. “Sometimes it seems keeping the world’s finances in order is a thankless task. We can at least take consolation in the knowledge it’s a Buddhist virtue, personal sacrifice for the benefit of others without seeking recognition.”

“The fastest way to universal transcendental enlightenment is more bankers in the world, I always say, self-sacrificing breed that they are,” quipped Plantin.

“Twenty years running this NGO and you still think of me as nothing other than a banker Jeaneé.”

“Oh ‘Romie, don’t be so sensitive. You know I’m only teasing, mon cherie.”

“Try as we might, we can never outrun our past. I should know, I have more past than just about anyone,” said Madame Bettencourt. Gerome, Plantin and Ásgeirsdóttir were lost for words. “It would be nice if people would let us move on. Instead, as the years go by all we seem to do is accumulate more of a past,” she added, pensively. “How is Lionél nowadays?”

Gerome looked at Liliane Bettencourt a moment bewildered. “Lionél Rochefort passed away, sadly. He was a great man, a great boss.”

“Mon dieu, such terrible news. How did it happen? When?”

“Let me see… September ’93 it was. Almost eleven years ago now,” explained Gerome sombrely.

When entrees arrived it was Plantin’s cue to take the rostrum, and Ásgeirsdóttir was able to gently suggest they take their seats.

Though humanitarian aid was not core business for UNESCO, Gerome owed his prominent position this evening to the intervention of Liliane Bettencourt, who was attending both as a major sponsor and as representative of the Alliance Internationale des Femmes. On accepting UNESCO’s invitation to this gala event, eighty-one year old Bettencourt requested the guest list so she could indicate her preferred seating arrangements. ‘Preferred’ actually meant who she would have at her table. She was both relieved and heartened to find Gerome’s name on the guest list, somebody with whom she could be comfortable, whose past association with her ailing husband provided warm reminiscences of happier times, and with whom she’d shared many an event like this one in days past.

Pop star Jenifer found herself within the most élite circle of this exclusive event on account of young Jean-Victor Bettencourt-Meyers being a fan. Reviewing the guest list with her personal assistant, coming across the name ‘Jenifer’, Madame Bettencourt had remarked “Jenifer who?” Her PA tried very hard to explain why it was just ‘Jenifer’ to no avail. “Who on earth has the name ‘just Jenifer’?” When her PA remarked that her grandson Jean-Victor was listening to Jenifer all the time, Liliane hatched the plan to have him accompany her and surprise him by having the beautiful young songstress seated right beside him. It had to be said, among all the dazzling beauties and starlets circulating so far this evening, the lad’s eyes appeared compulsively drawn to the singer, who in a vintage Bulgari dress and with Prada accessories cut an improbably unique and striking figure upon this sea of glamour. As he and his grandmother took their seats his heart indeed skipped a few beats as it became clear he was to be seated beside Jenifer, who’d been making introductions with Alan and Felicity.

“Madame Bettencourt, let me introduce Mister Alan Steiger, our chef de mission in Iraq, and Docteur Felicity Beauvoir, who will be flying out to our Iraq mission tomorrow to take up a position as surgeon.”

Madame Bettencourt nodded her assent and smiled.

“Oh,” said Jenifer. “You work in Iraq?”

“Oui.”

“And you must be?” said Madame Bettencourt, feigning ignorance.

“Jenifer,” said Jean-Victor.

“Bonsoir.”

“Oh this is Jenifer? You have a beautiful voice ma chère,” said Madame Bettencourt, who couldn’t actually recall hearing the pop music that came from this dark-eyed nubile, merely the genre. “My grandson Jean-Victor listens to you all the time.”

“I have your CD,” said the teenager, smiling ear to ear.

“Oh. That’s wonderful,” replied the young pop star. “You’ll have to let me sign it for you.”

The boy’s face went ashen. “I don’t have it with me,” he said, as though a great travesty had occurred. “I… I didn’t know you’d be here.”

“I have a new one coming out in a couple of months so how about if I send you a signed copy?”

“Oh, really? That would be wonderful,” said Jean-Victor utterly smitten.

“Docteur Beauvoir?” said Madame Bettencourt, considering. “Any relation to…?”

“Yes, he’s my father,” replied Felicity.

“Oh. I see,” said Madame Bettencourt, forcing a smile. Felicity smiled back.

“And I am very pleased to meet you,” said Gerome reaching across and shaking Jenifer’s hand before taking his seat opposite Liliane Bettencourt at the end of the table. “We’re very thankful for your support.”

“I’m very proud to be involved.”

“Oh,” said Madame Bettencourt, caught off-guard. “You’ve made a contribution to Gerome’s charity?”

“In such a troubled world I think his NGO does very important work. I’m just honoured that you’re personally aware of my donation, Monsieur Trembleau.”

“Very commendable of you ma chère,” said Madame Bettencourt, providing a polished performance of disguising her irritation.

Gerome could barely conceal his glee as he leaned back in his chair introducing Berglind Ásgeirsdóttir to Jenifer, Alan and Felicity. This was turning out better than he could have imagined. All he had to do now was publish an article in Le Figaro commending the young star for her generous contribution. Liliane Bettencourt could never allow herself to be outdone by this week’s celebrity nymphette, and the donation would be quadrupled.

“Well this year with your generous support we’ll be helping these two provide food, shelter and medical care to the terrorised women and children of Iraq,” Gerome told Jenifer, tilting his head toward Felicity and Alan.

Conversation halted as Jeaneé Plantin got the evening’s formalities underway.

“Mesdames et monsieurs,” she said, taking the rostrum. “On behalf of UNESCO Social and Human Sciences I welcome you to this evening’s charity gala event as part of our International Symposium on Gender, Peace and Conflict.” She paused to allow her intrusion into the hum of conversation to settle over the gallery, beaming theatrically at no one in particular, an orator of phenomenal technique as Gerome recalled.

“Firstly I would like to thank Madame Noëlle Lenoir, Minister for European Affairs, and Mr Osman Topčagić, Director of the European Integrations Directorate of Bosnia and Herzegovina for joining us here tonight. I’d also like to acknowledge Christine Albanel, President of the Museum and Domain of the Palace of Versailles, and thank you and your staff for preparing this marvellous venue.

“How lucky we are on such a beautiful evening,” she continued after a moment, smiling directly at a random few faces at the tables around her. “…to be here at this magnificent place. It’s one of the best things about working at UNESCO, the role we play in the recognition and preservation of the cultural and natural wonders that constitute our World Heritage list. But of course we have no more claim over them than anyone else, they represent a common heritage, they belong to all humanity and indeed in many ways, particularly those natural wonders, they transcend even humanity. As a Frenchwoman though, I reserve the right to claim Versailles as especially mine.”

She swayed backward ever so slightly before leaning forward as though she were Maria Callas taking a breath before launching into a new verse.

“Civilisation,” she declared, “…is a term we don’t use much anymore outside the ancient history classroom. Historically its usage was tied to the inverse concept of the ‘primitive’, and thankfully we no longer look at the magnificent achievements of our own cultures,” she said, allowing herself a moment to look across the Cotelle Gallery and absorb it, “…and use them to define the uncivilised, the ‘primitive’, to identify the lesser human beings, the social and cultural ‘untermunchen’.” She paused again momentarily to allow her use of the term to sink in.

“So we moved beyond the term ‘civilisation’ to demonstrate we don’t see ourselves as exceptional, or more accurately that we don’t see others as unexceptional.”

“I favour bringing back the term civilisation as a means of introducing a new counter-concept, de-civilisation. Yes, easy to forget that ‘civilisation’ is not essentially a noun.” She looked over at the party at the head of the table to her left. “Perhaps no-one here will have a more intimate appreciation of what I mean by de-civilisation than our Sarajevan visitor, Mr Topčagić [Topcagic’s own story of Bosnian war.]

“Three hundred years ago an ailing Louis XIV was visited here at the Grand Trianon by his five year old grandson. The Sun King told young Louis XV to keep France in peace for ‘it is the ruin of peoples!’

“Of course, Louis XIV’s conclusion was no semi-divine flash of brilliance. Actually it’s a pretty ordinary thing to say. Like me you probably know numerous people who say much the same thing all the time. I’d even dare to suggest most of you here tonight are in agreement with the Sun King. Yet peace is so often mislaid and this universal lesson about conflict all but forgotten.

“How is it that despite an indelible connection to our past and all the historical examples that are well remembered, successive generations forget the universal detriment brought by conflict? It’s because the lesson is not about peace or conflict, it’s about the ethno-centric assumption of exceptionalism. One thing that UNESCO’s World Heritage List demonstrates is that all peoples and all lands of the world are exceptional.

“Sadly, much of the work of UN agencies and their partners is in damage control – dealing with the consequences of conflict, most often, overwhelmingly in fact, the consequences upon women and children.

“Uniquely among UN agencies, the natural role I’ve come to realise for UNESCO to play is instead to develop, encourage and exploit civilising influences as a force for prevention. Women, it would seem, have a unique stake in this. Firstly, as I mentioned, we’re a disproportionate representation among recipients of humanitarian aid, the victims of conflict if you like and all of its ghastliness including sexual violence, displacement and insecurity, but women also represent an increasing proportion of active players in conflict, as in much of the world women are taking an increasing role in the military. Women are taking part in irregular offensive action too. You’ll find women among the FARQ guerrilla fighters in Colombia, and among suicide bombers in the Middle-East.

“In nations across the world, and yes this includes the developed world, women are only just starting to become players among the political elite from whence the genesis of conflict inevitably comes. We’ve new powers of influence women have seldom known before. The questions is – are we really going to be a civilising influence, a force for peace? I’d like to think so, not because of any assumptions about the innate pacific qualities of womanhood, simply because the gender balance is the biggest change in the dynamics of conflict since classical times.

“Despite rhetorical if accurate assertions that men are responsible for more acts of violence, it doesn’t logically follow that empowered women are any less likely to deliver conflict. It is a comforting thought though, an idea we’ve been trying to imagine ways to employ in the cause of peace since at least 2400 years ago when Aristophanes wrote Lysistrata.”

She paused as a few sniggers echoed around the gallery. Smirking, she continued. “What it does guarantee however is that we have a seat at the table as conflict is being played out and perhaps more importantly during peace-building.

“So what evidence is there to be optimistic that the increasing influence of women is going to be a force for civilisation, or more accurately, against de-civilisation, when for example in so much of the world women remain powerless? Well, that’s what I expect to find out through the course of this week. The implication of an increasing influence of women on conflict and peace is a theme among many of the speakers and papers being presented at this symposium. Of course it’s not the only theme.

“Already at this symposium we’ve heard Dr Eugenia Date-Bah explain both the importance and opportunity that exists in the appropriate employment of women in post-conflict reconstruction and the effect it has on the sustainability of peace building and nation building.

“Those of us lucky enough to have been at UNESCO House this morning to hear Betty Reardon speak will be utterly persuaded of the role gender can play in non-violent conflict resolution, and how important equity in education is in achieving that.

“Looking ahead at the programme for the rest of this week I am overwhelmed with anticipation. Thank you, each and every one of you for coming to make our symposium a success.

“I will wrap up now, not because I don’t have a lot to say on the subject but because while I watch you all savouring your entrées I see my own getting cold over there.” She garnered a few chuckles, particularly among those who knew she could talk the leg off an iron stove.

“After dinner we’ll have an opportunity to circulate a while before I introduce Minister Lenoir who has some interesting news about European intergovernmental initiatives, and Mr Topčagić who will share some experiences of the Balkan wars, Europe’s last major conflict. Please, enjoy the evening.”

Gerome stood amid the clapping, kissed Plantin on the cheek as she returned to their table before sliding her chair beneath her as she took her seat at the head of the table between himself and Madame Bettencourt. When applause subsided and guests turned to the extravagant meal being laid out before them an orchestra of conversation quickly engulfed the Cotelle Gallery. For Plantin’s benefit Gerome made introductions again.

“I understand your father’s Algerian,” said Madame Plantin to Jenifer.

“Oui,” said Jenifer. “My complicated heritage has been one preoccupation of the media, but my Algerian father is often the topic of conversation.”

“It’s something you have in common with Docteur Beauvoir here,” said Gerome.

“Your father’s Algerian too?”

“My grandmother. My grandfather was a Lieutenant in le Legion, he came home from North Africa in ’55 with an Algerian bride and a young son.”

“A Legionnaire?!” Madame Bettencourt reconfirmed with glowing admiration, being of that last generation to have known the French Empire and the rugged national symbolism of le Legion. “Soon after he was elected to the National Assembly my husband sat on the commission for overseas territories. In 1955 the Legionnaires in Algeria were a major point of discussion in our household,” Then her smile turned into a frown as a memory had her aghast. “So your grandfather was not among that rabble involved in the Officer’s Putsch in 1961?”

“No,” said Felicity with a laugh. “He was back home in Valbonne growing fruit by then,”

Reassured, Bettencourt smiled and nodded assent.

“Growing fruit in the Cote d’Azur? Sounds like an idyllic vocation for a retired soldier,” Plantin commented.

“How romantic,” agreed Jenifer.

Conversation over dinner covered the backgrounds of everyone except Liliane Bettencourt, Gerome and Jeaneé Plantin, from Jean-Victor’s planned university studies and Jenifer’s forthcoming second album, to Felicity’s work in the South Pacific and Berglind Ásgeirsdóttir’s yearning for snowfall. It finally settled upon Alan’s mission in Iraq and comparisons with those earlier conflicts like the Algerian war.

“How rudimentary humanitarian efforts were back then, and how challenging it must have been,” commented Ásgeirsdóttir.

“Well, most of what we need to do is rudimentary stuff – clean water and food, clothing, shelter and basic medical care,” said Alan, who’d reluctantly been drawn into conversation. “We may be better resourced nowadays but bureaucratisation has added its own difficulties, we’ve added layers of inefficiency that simply weren’t there before. How much less of my day would be consumed by administration around politics and accountability, and how much more of our time would have been spent delivering humanitarian aid if we’d been doing this for instance in Algeria in the ‘50s?”

This gave the party something to ponder over the haute cuisine and superior wine being lavishly served them.

As meals were coming to an end several guests started moving around and visiting acquaintances, and all around the Cotelle Gallery parties began to form. Gerome, Plantin, Bettencourt, Ásgeirsdóttir and Jenifer were soon very occupied, so that Felicity, Alan and Jean-Victor were left to form their own little party in the recess of a window overlooking a geometric garden toward the Grand Canal, in between Jean Cotelle II’s Vue de l’Orangerie et du château à partir de la pièce d’eau des Suisses and his Bosquet de l’Arc de Triomphe-Salle basse. Felicity’s two gentleman companions were reserved to say the least. Jean-Victor forced a comment on the nearby painting of l’Orangerie.

“It’s very nice,” he said inanely.

“Yes it is,” agreed Alan, stepping over to take a closer look at its surface, imagining that yes, that is what a 17th century oil painting looks like close up.

“The garden looks exactly the same today,” said Jean-Victor.

Felicity smiled as the two men looked on awkwardly at the painting, as though imagining they were making the impression of consumedly appraising an exquisite masterpiece but in fact using the gesture to avoid conversation with anyone else in the crowd.

“It’s an interesting idea isn’t it, art imitating life and then life being artificially held still so that it conforms thereafter to the art,” said Felicity.

Both men nodded and said hmmm… as though considering her appraisal in depth.

“His work hangs all around the gallery,” Jean-Victor said stiffly.

“How much would paintings like that be worth do you think?” Alan pondered, feigning interest.

“I don’t know,” said Jean-Victor, who hadn’t yet developed the knowledge of art acquisition that he would no doubt one day need. “All together they must be worth a couple of million euros,” he surmised, gesturing at the paintings hanging the length of the Cotelle Gallery.

As Felicity followed her disinterested companions’ eyes around the gallery she couldn’t help observing that was approximately the value of her own father’s work presently on display. She nudged Jean-Victor with an elbow. “See Pierre Cabot over there,” she said, lowering her voice and nodding discretely toward the veteran action movie star. Her two companions leaned closer to hear.

“Yeah,” said Jean-Victor attentively.

“Three facelifts,” she whispered.

The boy’s eyes widened, and Alan’s no less, as they both glanced compulsively toward the star.

“Helene Cardinale over by the rostrum,” she continued, pointing out the former fashion model and now department store figurehead. “Frequent flyer kilometres on the liposuction table.”

“Nooo?!” said Jean-Victor in amazement.

“Yes,” said Felicity nodding. Alan blinked in astonishment. “My father’s a cosmetic surgeon,” she explained.

“He is?”

“Aha.” Felicity nodded discretely toward various celebrities and other identities around the gallery. “Breast enhancement… nose-job… botox… tattoo removal… breast enhancement and botox… facelift… lipo’… breast reduction,” she rattled off.

Alan frowned at the last one “Really?”

Jean-Victor giggled.

Henri Beauvoir grew up the eldest son of a Southern orchardist and bee-keeper, the former Lieutenant of the Foreign Legion. His Algerian mother moved to her Lieutenant’s native Provence at a time when Algeria was still considered part of the French mainland. In the decade after France’s North-African territory gained independence in 1962, Samira Beauvoir became increasingly culturally isolated. Intensely proud of her heritage, she’d often find cause to declare so in her dealings with the townsfolk of Valbonne where they’d settled. While appreciated by her husband and many leading community figures, among Valbonne’s more parochial inhabitants, who took the view that Algeria was a land of towel-heads and turncoats, she was often the butt of racial slur. This perhaps contributed to a sense of restlessness in the young Henri.

His father’s orchards and apiaries delivered the family an adequate if somewhat hardworking existence, but Henri’s ambitions were not quite so modest. By his late teens he was making the daily and nightly commute downhill to the resort towns of the Cote d’Azur where he worked in the cafes and hotels. A determined worker with an outstanding eye to detail, he soon found himself working in the most exclusive hotels serving Europe’s most affluent, for whom the Cote d’Azur was a favoured playground. With his mother’s dark eyes and brown skin, his father’s lean muscular frame, and his own unique intensity and highly developed sense of self-possession, Henri found popularity among the region’s transitory patrician inhabitants who saw him as another exotic Mediterranean attraction, and he was often invited to parties as a curiosity, a touch of local flavour. Many of them returned year to year including a family from Normandy who possessed a villa in Antibes, a berth in the local marina, and a wild blonde blue-eyed daughter named Blanche who represented Henri’s own idea of the exotic.

The relationship was seasonal for a few years, an open secret, and did not continue at a distance whenever she returned home to Rouen. While the family discreetly accepted Henri as Blanche’s holiday play-thing, any suggestion that a courtship was occurring would have been quite absurd. Henri was the pleasant young local who took your breakfast orders or served you Long Island Iced Teas at le Martinez.

Henri understood all too well his social limitations and it rankled. What they often mistook for an endearing nonchalance was in fact a great big chip on his shoulder.

This all changed though in 1971 when Henri’s father concluded negotiations with the agency funded by both national and provincial governments for the acquisition of land for the establishment of the enterprise estate, Sophia Antipolis. Great tracts of land through the middle of this planned sprawling new technology park were occupied by the former Lieutenant Beauvoir’s prized orchards and apiaries. Monsieur Beauvoir retained small landholdings outside of Sophia Antipolis, but his compensation was of such proportion that any agriculture he undertook hereafter was essentially as a hobbyist.

Now almost twenty, first son Henri who’d been both smart and conscientious during his schooling, matriculated without difficulty and was dispatched to Paris to study medicine. Never again would Henri suffer the barbs of his mother’s race or his father’s income. Never again would he be subject to social stigma. Or so he thought.

Henri’s escape from the small town of his childhood coincided with Blanche outgrowing her own provincial beginnings. They ran into each other by chance at a café on Boulevard Saint Germain. Both liberated by the boundless opportunity that Paris represented, and somewhat assisted by the times, their once teenage urges for each other now re-ignited in an explosion of passion, the consequence of which was the arrival two years later in 1974 of a bounding baby Felicity. A marriage did occur, and it saw out the decade, but just as Henri reacted to his former modest social standing by becoming exceedingly conservative, Blanche reacted to her own staid Northern upbringing by submersing herself in Paris’s avant-garde fashion, art and music scene, finding her feet at precisely the punk rock era. Though finally if informally separated since 1984, they remained technically married right to this day, more as a result of oversight than of lingering attachment.

Henri’s determination was such that he was able to enter the competitive discipline of surgery, and he pursued the then still somewhat obscure but already lucrative specialisation of cosmetic surgery. Incredibly, right from his internship he found himself catering to the same class and sometimes even the same individuals he’d served cocktails and lunches to less than a decade before. The same remarkable work ethic and attention to detail he’d displayed back then guaranteed that Henri soon earned a reputation and eventually even an income to rival most of them. By 2004 Henri knew a good proportion of France’s, indeed Europe’s ruling classes more intimately than almost anyone, making him as well connected and deeply respected as anybody at UNESCO’s event tonight at Versailles. But Henri would never, could never be invited to an event such as this. His relationships with these people were intensely private. Not one of them would hope to see him at an event like this, knowing as he did their most intimate secrets.

“Watch out, here comes your grand-mère with Tummy-tuck,” said Felicity as Bettencourt bounded toward them with Jean-Pierre Gaumont, head of StudioCanal trailing.

“Jean-Victor, there’s someone I want you to meet,” said Liliane. “See, Jean-Pierre, isn’t he as handsome as I said.”

“Pleased to meet you,” said Gaumont, reaching for the young man’s hand. “Your grand-mère tells me you have an interest in cinema.”

“Well I’m not sure I’ve yet met anyone who doesn’t,” said Jean-Victor, shaking the studio boss’s hand with a broad smile. Unable to control the urge he glanced down at Gaumont’s waistcoat, then burst into laughter.

“And you must be…” said Gaumont, releasing young Jean-Victor’s hand and turning to Felicity and Alan.

“Docteur Felicity Beauvoir.”

“Pleased to meet you,” said Alan, taking Gaumont’s hand with a grin. “Alan. Alan Steiger.”

For the rest of the evening Alan, Felicity and Jean-Victor were inseparable buddies, sharing as they did a gentle comedic disdain for the pomp of the event. As they circumnavigated the gallery they garnered a few of their own discreet commentators. Whispers of “Bettencourt’s grandson” were followed by subtle alluring stares from glamorous lasses and one or two cougars. The singularly understated elegance of her olive-brown George Hameika dress and tiny pendant of simple Arabic design, her uniquely naturally tanned skin and the sun-bleached tips of her hair, at the end of winter no less, contrasted against both the lustre of her gold Christian Louboutins and the orangeness of some of the more radiant ladies, unassuming as it may have been, marked Felicity as quite astonishing all the same.

“His suit hangs off him like a potato sack and the trousers don’t match the jacket,” Liliane Bettencourt herself observed piteously of Alan. She imagined him the hard working school teacher of humble middle-American origins, scouring the racks at charity bazaars, carefully accumulating his wealth in food stamps until lifted from menial obscurity by a benevolent Gerome. She would make a point of taking him aside at some point in the evening and making her €5 million NGO pledge directly to Alan. Gerome would be enormously impressed and thankful for her altruism.

Vue de l’Orangerie et du château à partir de la pièce d’eau des Suisses – Jean Cotelle the younger

an author making fun of tropes, if they do it well. Cervantes and Don Quixote comes to mind.

an author making fun of tropes, if they do it well. Cervantes and Don Quixote comes to mind. brimmed cotton hat and gardening gloves impeccable despite the pile of leaves he and his buddy had amassed. ‘Kaba Kuneguchi’, he would write in my notebook, ‘September 30th, Heisei 23’ (2011), in hiragana to make it easy for the gaijin. I’d been circling the Miura Anjin memorial for ten minutes taking photos from outside the tall iron fence. Kaba was a volunteer with the Tsukuyama Park Preservation Society. Officialdom. It was okay.

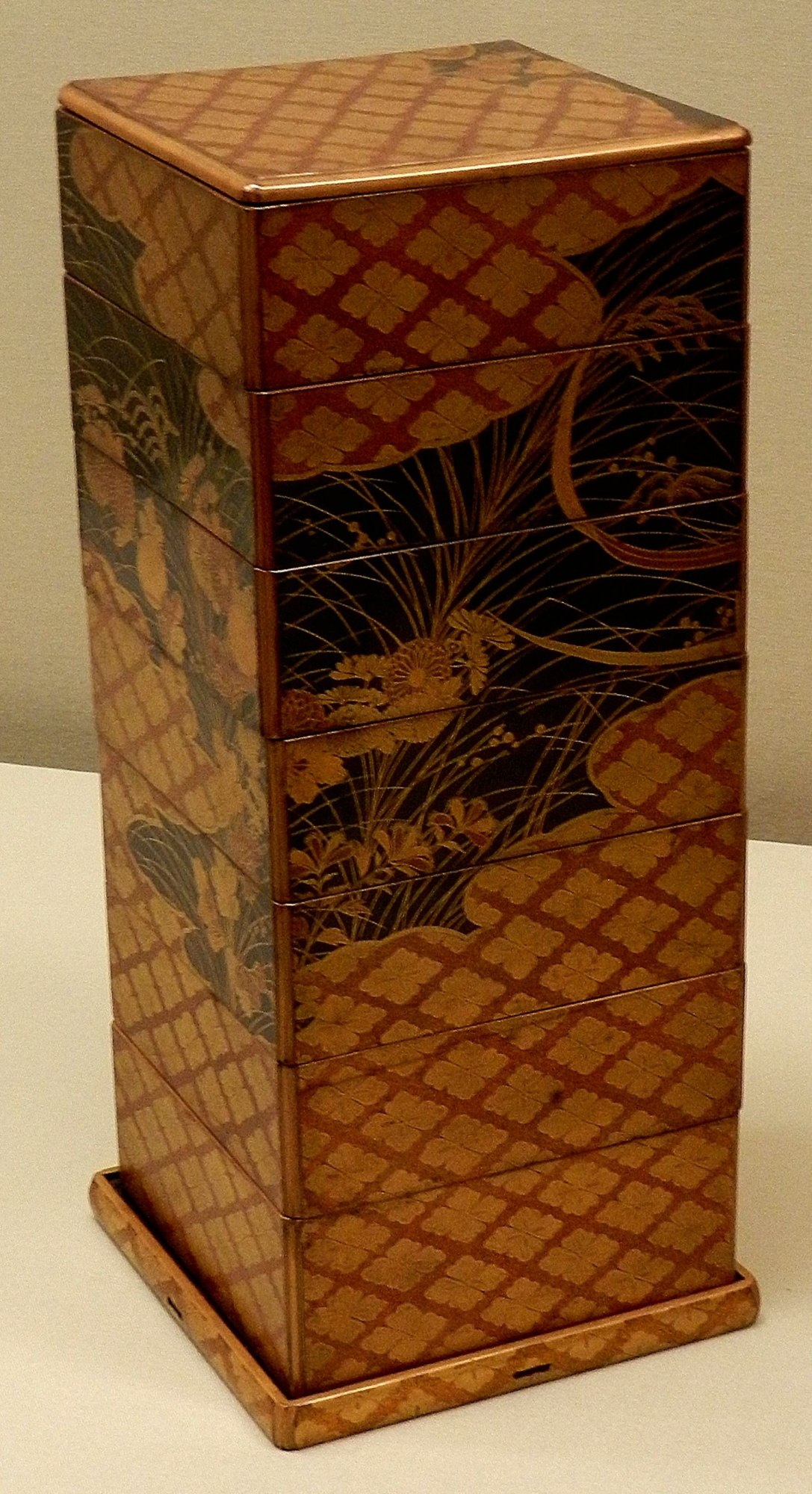

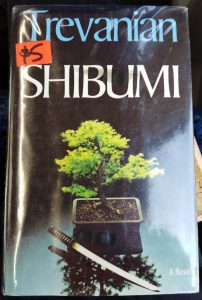

brimmed cotton hat and gardening gloves impeccable despite the pile of leaves he and his buddy had amassed. ‘Kaba Kuneguchi’, he would write in my notebook, ‘September 30th, Heisei 23’ (2011), in hiragana to make it easy for the gaijin. I’d been circling the Miura Anjin memorial for ten minutes taking photos from outside the tall iron fence. Kaba was a volunteer with the Tsukuyama Park Preservation Society. Officialdom. It was okay. Around that time, I read Trevanian’s Shibumi, a broad, brooding novel. Shibumi revealed to a fifteen-year-old that there are alternative frames through which to look at the world, and that all knowledge is refracted by the conduits through which it’s conveyed. The novel also introduced me to the excitement of the political thriller. Protagonist Nicolai Hel was born in Shanghai to an exiled White-Russian mother, and raised in Japan by a surrogate father, General Kishikawa of the Imperial Japanese Army. It’s this upbringing, with an acute sensitivity to custom, honour, the aesthetic, and clean, lethal violence, that would equip Nicolai for a career as an international assassin.

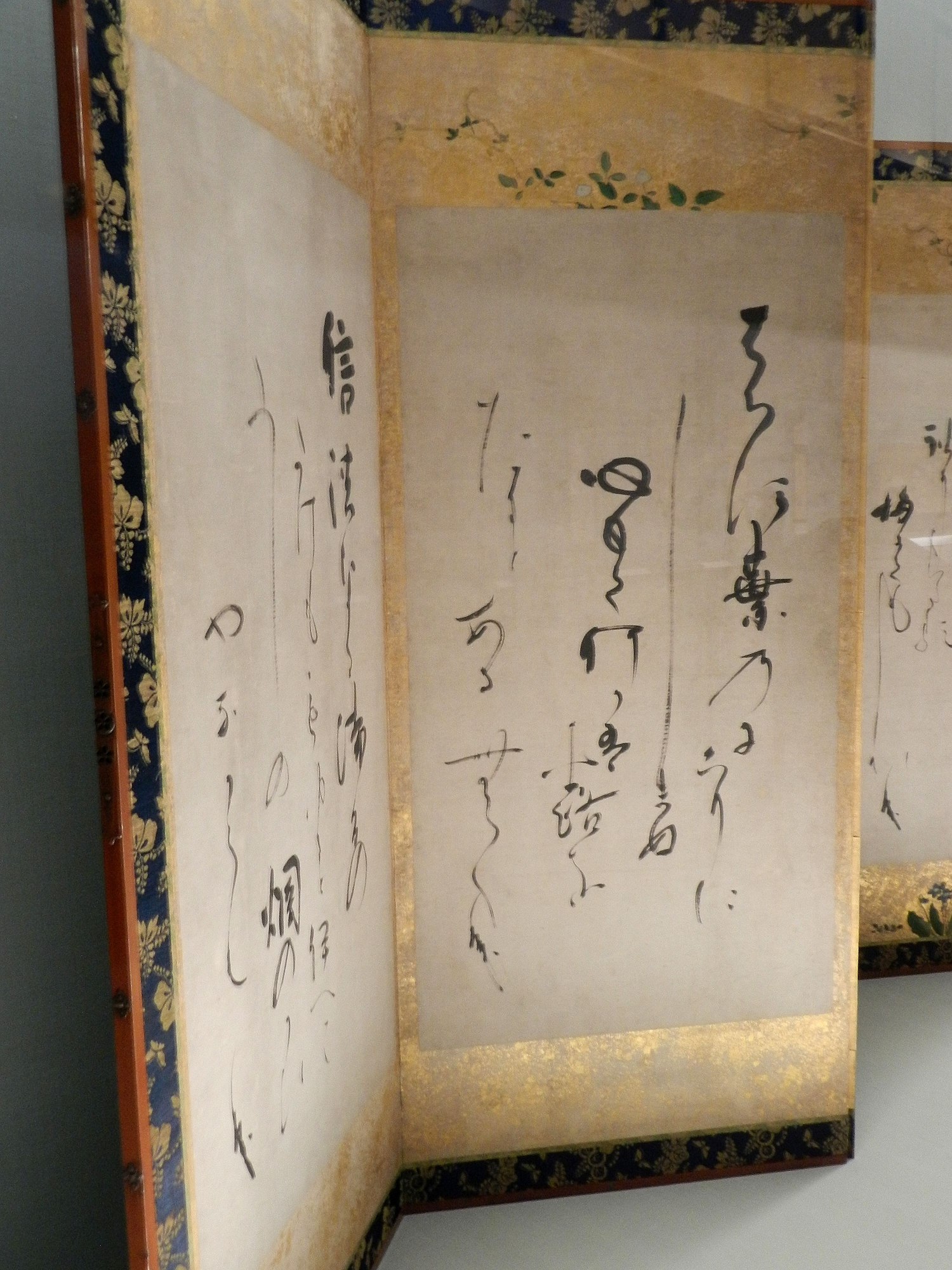

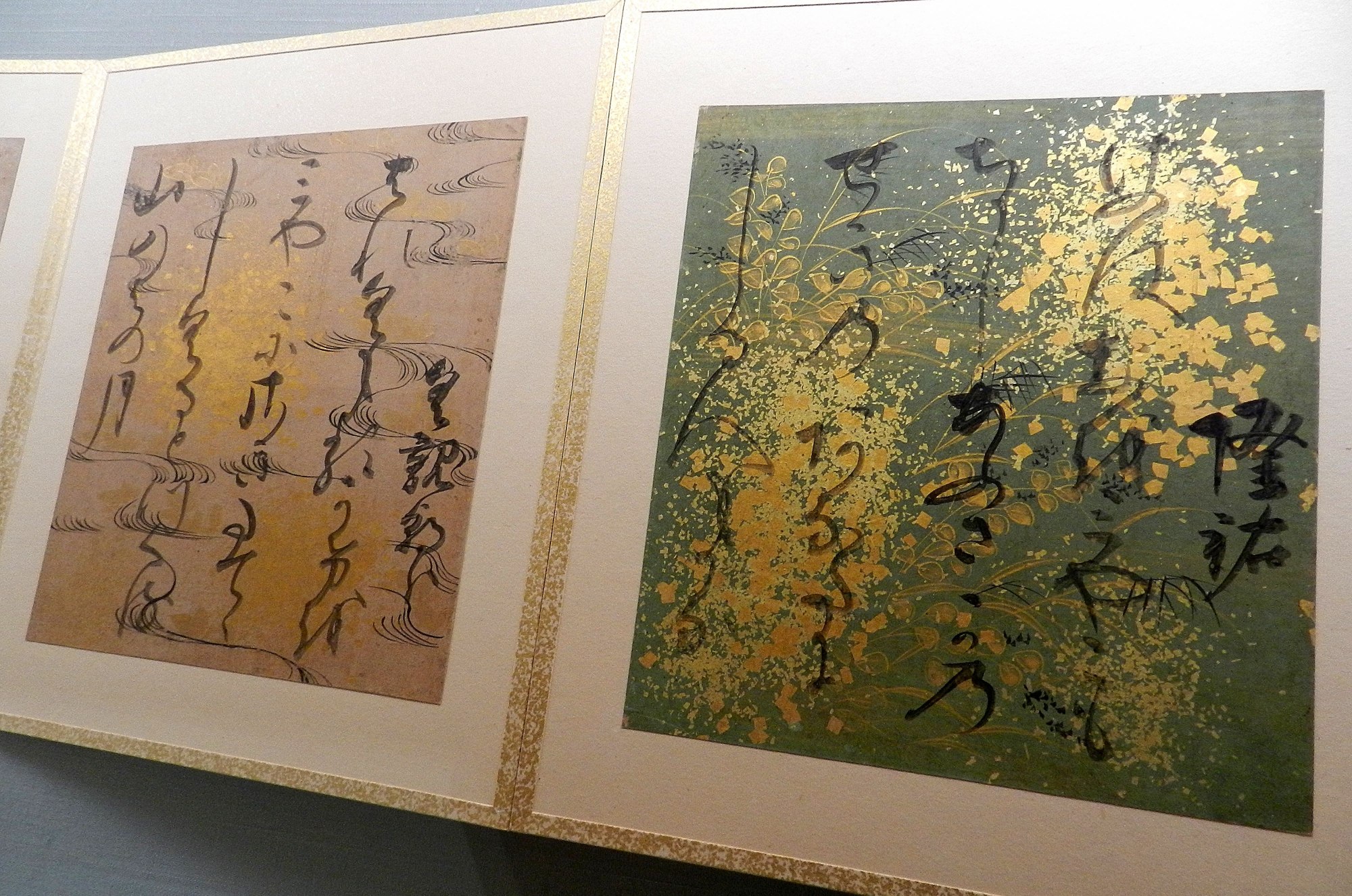

Around that time, I read Trevanian’s Shibumi, a broad, brooding novel. Shibumi revealed to a fifteen-year-old that there are alternative frames through which to look at the world, and that all knowledge is refracted by the conduits through which it’s conveyed. The novel also introduced me to the excitement of the political thriller. Protagonist Nicolai Hel was born in Shanghai to an exiled White-Russian mother, and raised in Japan by a surrogate father, General Kishikawa of the Imperial Japanese Army. It’s this upbringing, with an acute sensitivity to custom, honour, the aesthetic, and clean, lethal violence, that would equip Nicolai for a career as an international assassin. credited as the world’s first novel, and for her poetry and her diaries which provide a

credited as the world’s first novel, and for her poetry and her diaries which provide a into view, abstract forms in stone and yet full of humanity. One, with fluid edges and floral suggestions, was unmistakably feminine, the other, sharper edged with less organic accents, discernibly male. Here stood a man and woman in timeless consort. Side by side and full of vigour, the immigrant samurai and lady of Hemi overlooked their fief, and beyond it in the distance the metropolis once known as Edo. I’d stumbled across the mossy cenotaphs of Miura Anjin (William Adams) and Magome Oyuki. My guide map was in Japanese so I’d somehow not anticipated them, though I’d been following Adams’s trail. I wasn’t sure what I was looking for when I’d set out to find what I could of William Adams, but I knew this was it. Like Adams, and James Clavell’s John Blackthorne, I’d fallen in love with a Japanese. Like Adams and Blackthorne I’d fallen in love with the Japanese. In form and placement these

into view, abstract forms in stone and yet full of humanity. One, with fluid edges and floral suggestions, was unmistakably feminine, the other, sharper edged with less organic accents, discernibly male. Here stood a man and woman in timeless consort. Side by side and full of vigour, the immigrant samurai and lady of Hemi overlooked their fief, and beyond it in the distance the metropolis once known as Edo. I’d stumbled across the mossy cenotaphs of Miura Anjin (William Adams) and Magome Oyuki. My guide map was in Japanese so I’d somehow not anticipated them, though I’d been following Adams’s trail. I wasn’t sure what I was looking for when I’d set out to find what I could of William Adams, but I knew this was it. Like Adams, and James Clavell’s John Blackthorne, I’d fallen in love with a Japanese. Like Adams and Blackthorne I’d fallen in love with the Japanese. In form and placement these  cenotaphs eloquently captured Adams and

cenotaphs eloquently captured Adams and his benefactor, Tokugawa, in his retirement at Sunpu. Within Sunpu Castle Park survives a sprawling mandarin tree, planted by Ieyasu, that it’s easy to imagine could have borne fruit that Adams tasted.

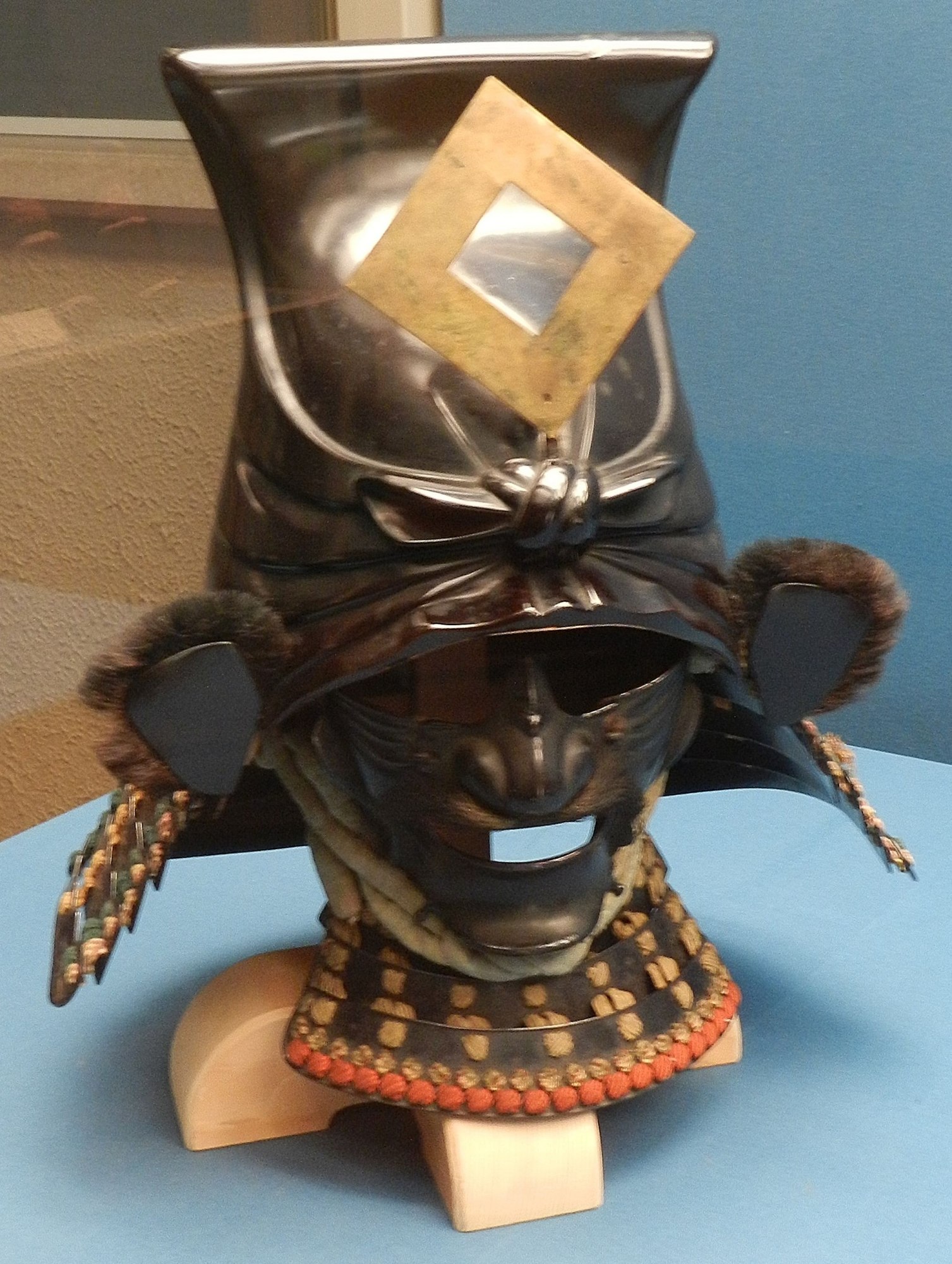

his benefactor, Tokugawa, in his retirement at Sunpu. Within Sunpu Castle Park survives a sprawling mandarin tree, planted by Ieyasu, that it’s easy to imagine could have borne fruit that Adams tasted. sword) and its vicious application, are preoccupations in Western imagery of Japan. They coincide with the orientalist notion of the savage, inscrutable, deadly ‘other’. Some Japanese will chuckle at this Western preoccupation, and it marks one as a ‘hen-na-gaijin’ (silly foreigner). I must keep my curiosity about these things in the closet.

sword) and its vicious application, are preoccupations in Western imagery of Japan. They coincide with the orientalist notion of the savage, inscrutable, deadly ‘other’. Some Japanese will chuckle at this Western preoccupation, and it marks one as a ‘hen-na-gaijin’ (silly foreigner). I must keep my curiosity about these things in the closet. once, who was being a rogue, “She won’t say anything. She’ll just hand you the wakizashi,” (the short sword with which one performs seppuku).

once, who was being a rogue, “She won’t say anything. She’ll just hand you the wakizashi,” (the short sword with which one performs seppuku). on which they’d drifted wretchedly into Japanese waters, was Pieter Janszoon, her shipwright. In Shogun, Lord Toranaga has Blackthorne’s successfully constructed first ship destroyed, breaking his hopes of sailing home to England. Another trope: the wily, manipulative oriental.

on which they’d drifted wretchedly into Japanese waters, was Pieter Janszoon, her shipwright. In Shogun, Lord Toranaga has Blackthorne’s successfully constructed first ship destroyed, breaking his hopes of sailing home to England. Another trope: the wily, manipulative oriental.

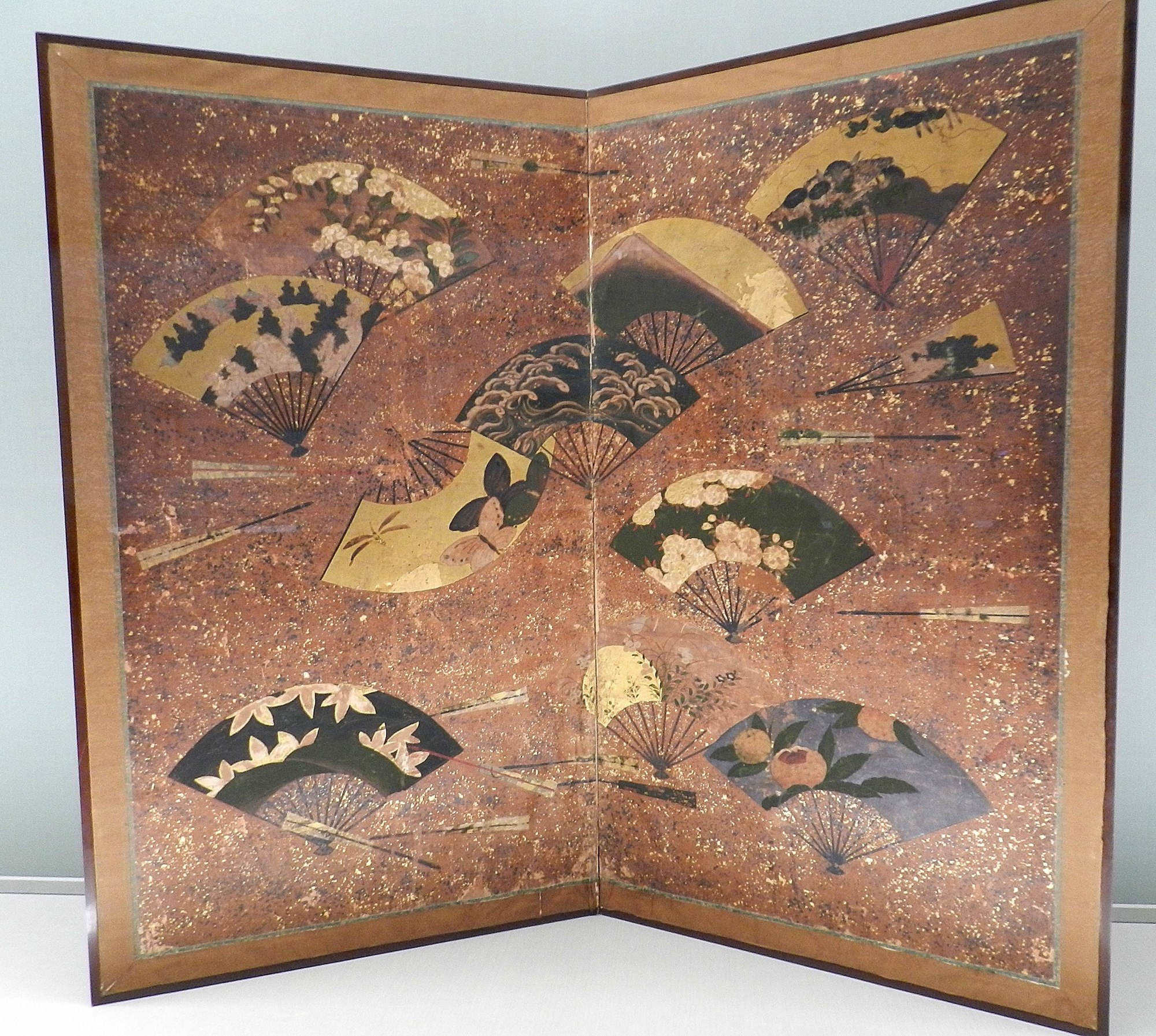

marriageable age and should be staying behind in the society of the capital, but she’s adventurous. She’s cultured in Chinese writing and its venerated forms of poetry, and she can go toe-to-toe with anyone in its customary use as word-sport. In her novel, Dalby explores this in her portrayal of a historical visit by a Chinese delegation to Echizen.

marriageable age and should be staying behind in the society of the capital, but she’s adventurous. She’s cultured in Chinese writing and its venerated forms of poetry, and she can go toe-to-toe with anyone in its customary use as word-sport. In her novel, Dalby explores this in her portrayal of a historical visit by a Chinese delegation to Echizen.

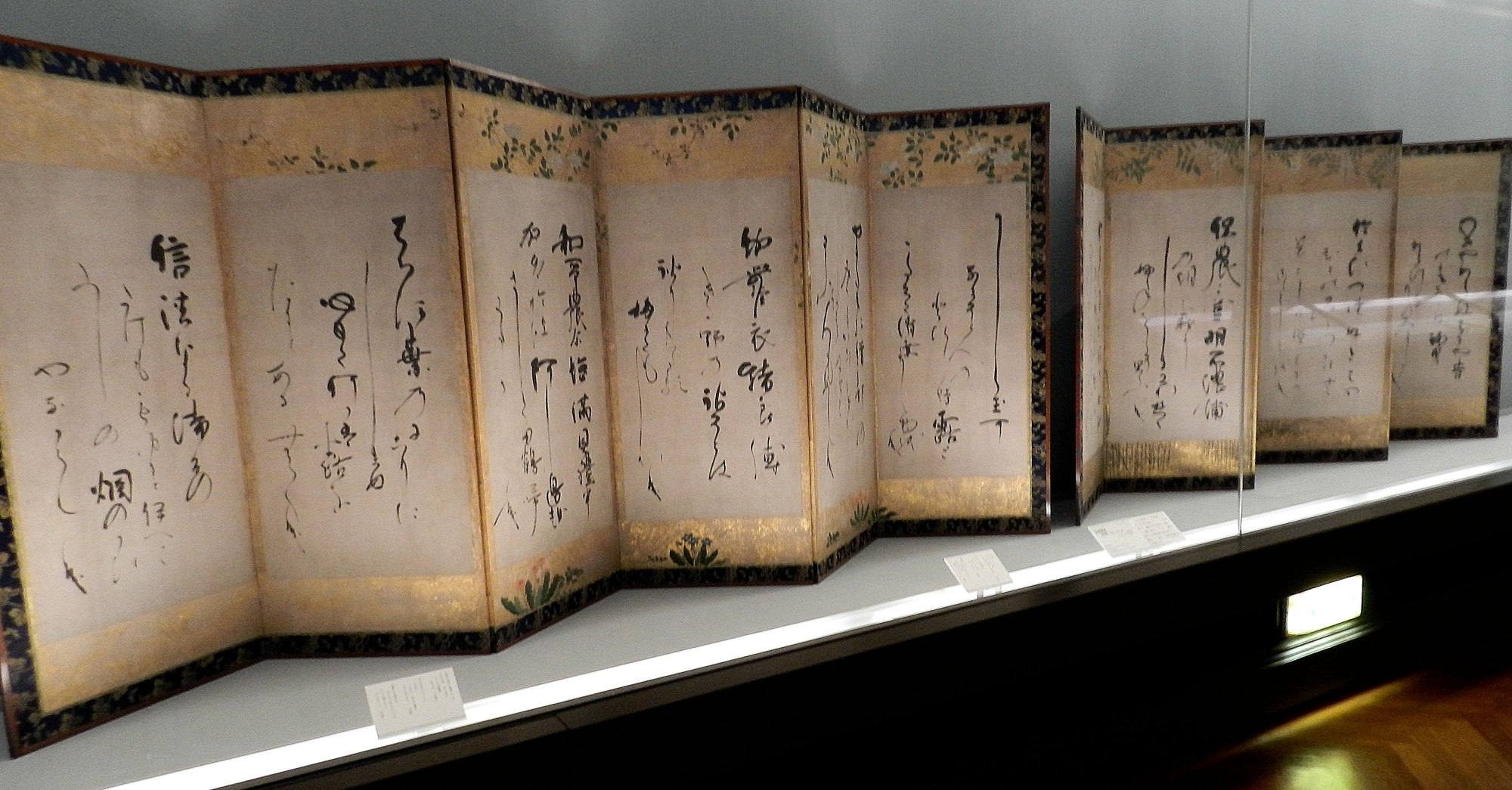

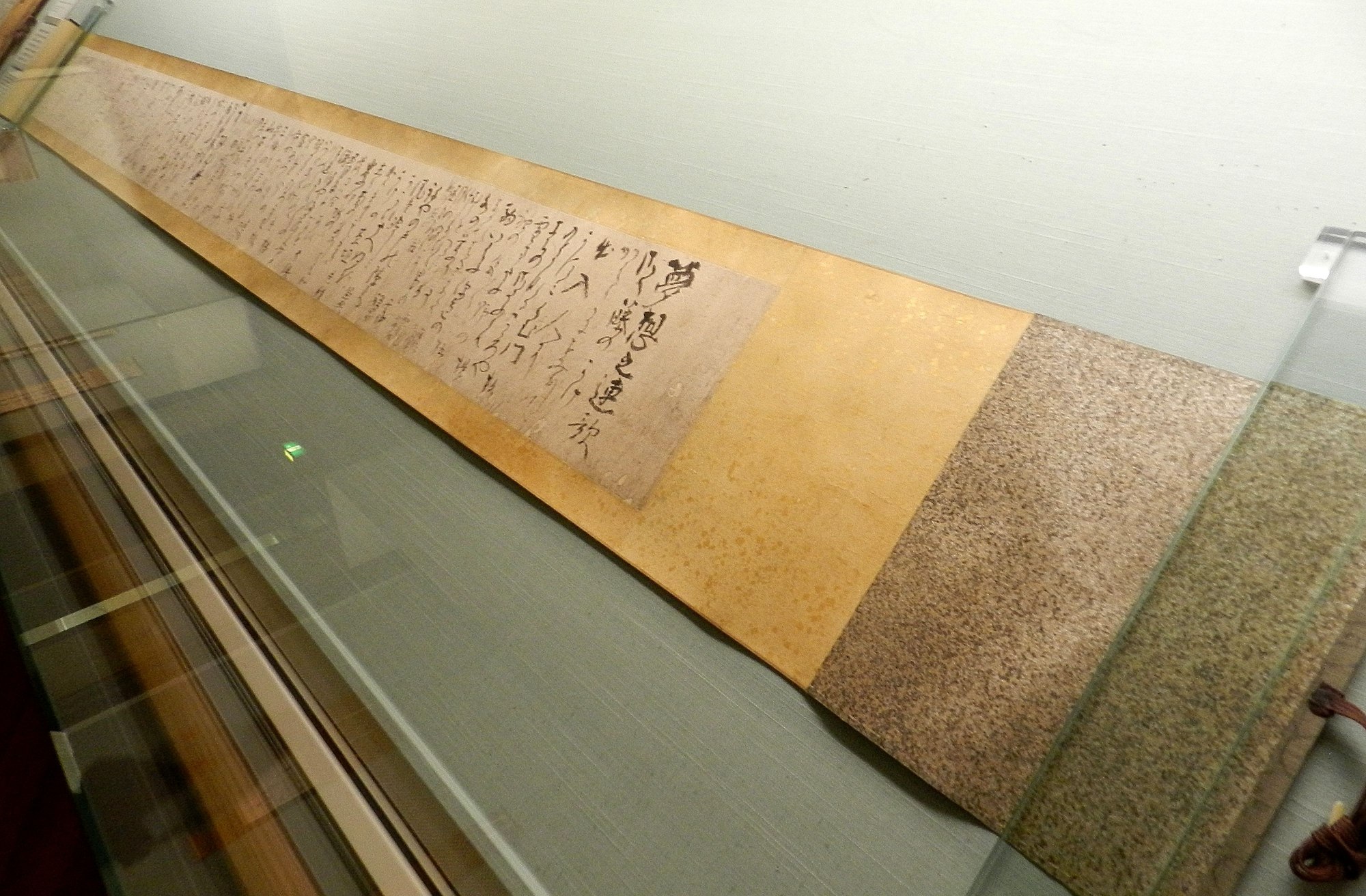

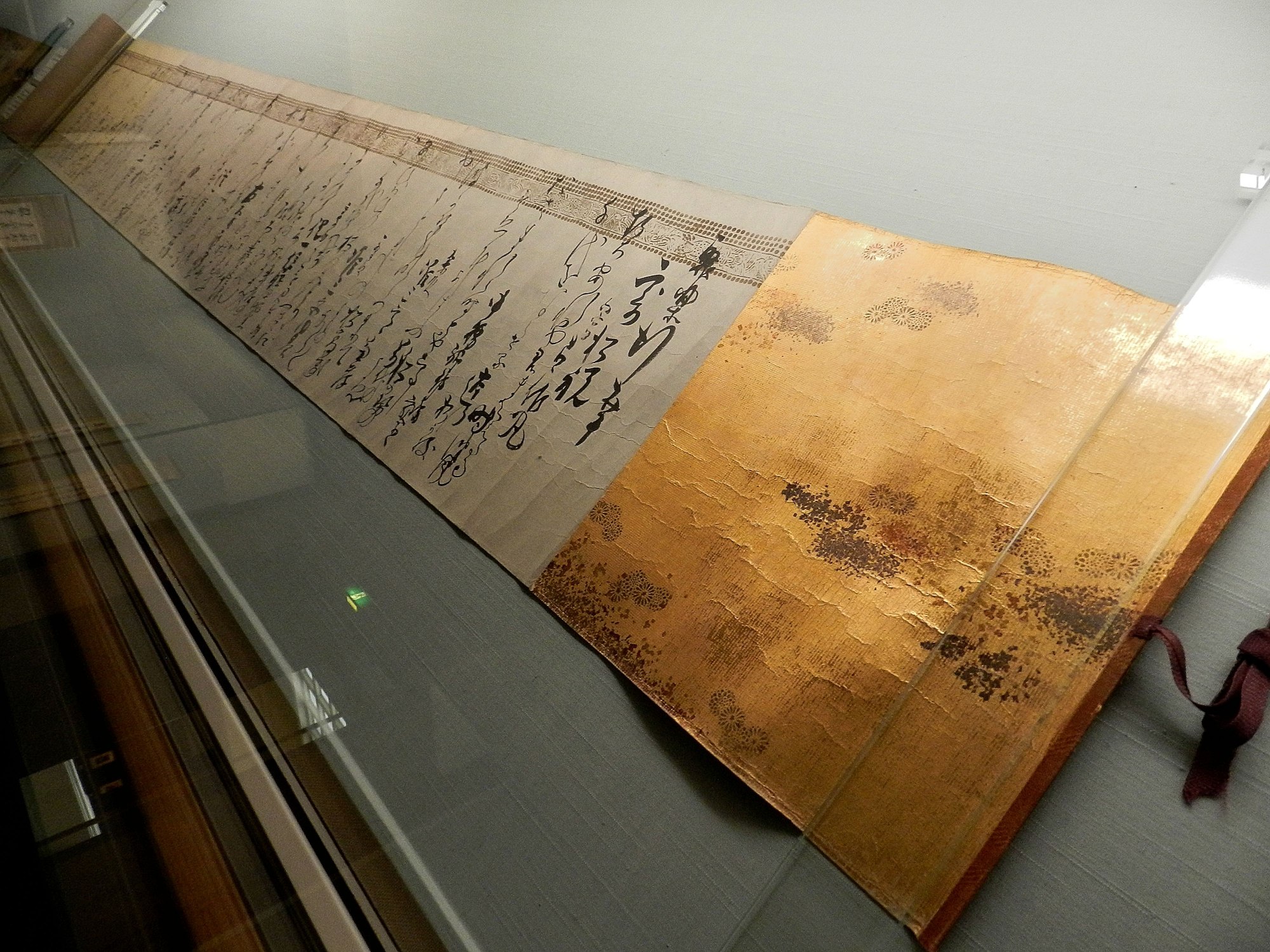

It’s most likely here a thousand years ago that Murasaki Shikibu wrote the first part of the Tale of Genji. It’s the site once occupied by the Tsutsumi-chunogon mansion, built by Murusaki’s great-grandfather, Fujiwara Kanesuke. Murasaki was born at Tsutsumi-chonogon and lived much of her life here. Her marriage in 998 was cut short by the death of her husband, Nobutaka, three years later. She moved from here to the court of the Heian imperial palace in about 1005 at the behest of regent, Fujiwara Michinaga, becoming lady-in-waiting to Empress Shoshi.

It’s most likely here a thousand years ago that Murasaki Shikibu wrote the first part of the Tale of Genji. It’s the site once occupied by the Tsutsumi-chunogon mansion, built by Murusaki’s great-grandfather, Fujiwara Kanesuke. Murasaki was born at Tsutsumi-chonogon and lived much of her life here. Her marriage in 998 was cut short by the death of her husband, Nobutaka, three years later. She moved from here to the court of the Heian imperial palace in about 1005 at the behest of regent, Fujiwara Michinaga, becoming lady-in-waiting to Empress Shoshi.

To sit and look over the Genji Garden, established in 1965, is to surrender your thoughts to a life lived on this spot a thousand years ago.

To sit and look over the Genji Garden, established in 1965, is to surrender your thoughts to a life lived on this spot a thousand years ago. death, when she turned her energies cathartically to her Genji monogatari, would she not have put aside her writing brush sometimes and, eyes cast over this very garden in its seasons, have meditated on the transience of life and love? In this earth are there not still traces of her incense, on the wind not faint reverberation of her poems?

death, when she turned her energies cathartically to her Genji monogatari, would she not have put aside her writing brush sometimes and, eyes cast over this very garden in its seasons, have meditated on the transience of life and love? In this earth are there not still traces of her incense, on the wind not faint reverberation of her poems? Lady Murasaki

Lady Murasaki

choosing? Taken by her stories of lustful encounters, and the underlying loneliness and yearning in her own story, I was enamoured with a woman who’d been dead a thousand years. Was she an orientalist ideal I sought in my Japanese wife? Am I another Westerner romanticising the exotic, unable to distinguish the temporal other?

choosing? Taken by her stories of lustful encounters, and the underlying loneliness and yearning in her own story, I was enamoured with a woman who’d been dead a thousand years. Was she an orientalist ideal I sought in my Japanese wife? Am I another Westerner romanticising the exotic, unable to distinguish the temporal other?

shaped stringed instrument, an instrument played by Murasaki’s protagonist, Genji, and Murasaki herself. On a suburban back-street we came across an antique store with battered biwa hanging from the walls and rafters in various states of disrepair. It’s the neighbourhood where, indelibly, I’d exchanged glances with a Maiko more than a dozen years before. Now that I think of it, it was during that visit to Japan that I met my wife, Chizuru.

shaped stringed instrument, an instrument played by Murasaki’s protagonist, Genji, and Murasaki herself. On a suburban back-street we came across an antique store with battered biwa hanging from the walls and rafters in various states of disrepair. It’s the neighbourhood where, indelibly, I’d exchanged glances with a Maiko more than a dozen years before. Now that I think of it, it was during that visit to Japan that I met my wife, Chizuru. Bryce and I cycle down to the site of Miura Anjin’s mansion in Nihonbashi, where there’s a little stone memorial, well-tended. We head over to the imperial palace, and circle the giant statue of fourteenth century samurai,

Bryce and I cycle down to the site of Miura Anjin’s mansion in Nihonbashi, where there’s a little stone memorial, well-tended. We head over to the imperial palace, and circle the giant statue of fourteenth century samurai,  Kusunoki Masashige, on horseback. We pass an oversized motor-scooter with blue flake-metallic paint and chrome to excess. It’s a Harley Davidson parody, incurably Japanese, and its swept back styling oddly mirrors the stance of Masashige’s thundering steed.

Kusunoki Masashige, on horseback. We pass an oversized motor-scooter with blue flake-metallic paint and chrome to excess. It’s a Harley Davidson parody, incurably Japanese, and its swept back styling oddly mirrors the stance of Masashige’s thundering steed.

as their taxi inched along. “We can take a shortcut through Marie Antoinette’s Estate.”

as their taxi inched along. “We can take a shortcut through Marie Antoinette’s Estate.”